Lists are like Marmite. You either love them or hate them. I’m definitely of the former persuasion. Like studying a good map, imagining how a ride will pan out and the gear I’ll need to endure it is a big part of what gets me fired up for an adventure. If that’s you, then scroll to the bottom for all the tiny details. If you’d rather stick pins in your eyes, then I’ll spare you the agony. Just consider the picture at the head of this article as the gear summary. Somehow or other, everything managed to squeeze into it’s allotted place on the bike. Of course the real test would be how well it rode, and whether all the new gear worked once out in the Scottish Highlands. Luckily, to help with that part, I have some properly wild country on my own doorstep, in the form of Dartmoor. Always beautiful, but in bad weather, also bleak and forbidding.

There – 10th July 2020

There was a great sense of satisfaction in seeing all the gear that had steadily accumulated in a cardboard box over winter finally assembled on the bike. Maybe it was because of all that anticipation, but I was suddenly nervous when the time came to roll off down the drive. Ordinarily, I’d have had Yoli chasing me out the door and telling me to get on with it. But she was out with Ben having their own adventure to IKEA and a nearby toyshop. So it was just me, standing there, dithering about whether I’d got everything, locked up, switched off the iron etc. After numerous re-checks, the sound of whirring freehubs did eventually echo it’s way along our street.

The first decision was which way to get out of Sidmouth – only one of the options involving no signiciant climb. In a moment of madness, I ignored the turn and made for Peak Hill, with its double digit gradient. The point being to prove the rationale of the dinner plate sized rear cassette. Did it, in fact, make a 20%ish gradient survivable with the fully loaded rig. Pretty much was the answer. It was a slog, and I did pause for breath and a couple of steps on foot just before the top, but that was largely caution about not burning too much fuel with the rolling climbs beyond Exeter still to come. For now though, out of the Sidmouth Valley, it would be easy riding down to the coast and along the Ex estuary.

Being familiar, didn’t make it any less delightful. The lovely trail along the old Budleigh branch line was busy with walkers and cyclists out enjoying the Friday afternoon sunshine, and it was much the same along the estuary path. It made one moment in Exton all the more comical. An old gent was out walking his dog. He was stood on the one side of the road, and his dog the other, the lead strung fully across the tarmac in between. I’m normally reluctant to ring my bell more than once for fear of seeming impatient, but in this case it was only the third or fourth shrill ding which woke the hapless chap out of his afternoon slumber. His next words were priceless:

“Oh, I’m so sorry, I’m not used to seeing cyclists along here.”

Seriously? A group of two or three riders had just passed me and couldn’t have been more than seconds ahead. And a family of at least four were barelling down the hill behind me. Not to mention at least five bikes I could see from that very spot parked outside the ice cream shop. Cyclists? On one of the best and most popular local cycle routes? Who could imagine such a thing! I just about managed to do the decent thing and wait for him to be out of earshot before bursting out laughing.

Beyond Topsham I wound through familiar housing estates. At some point, I heard the unmistakeable whoosh of deep section wheels powering up behind me and soon after flashing past. The rider’s physique may not have been as sleek and svelt as his Pinarello, but he was travelling way faster than me so I wasn’t exactly in a position to judge. It would have been a brief and unmemorable encounter, except that as I approached the start of the Exeter cycle lane he re-appeared coming back along the edge of the dual carrigeway the opposite way to the traffic. Clearly he wasn’t local, and we struck up a brief conversation whilst waiting for the crossing light to turn green. We exchanged remarks about our respective rigs: mine complimenting his racing thoroughbred; his enquiring where I was going so heavily rigged. We parted ways soon after. Once over the river my route headed along the navigation towpath towards the city center.

Twising my way through Exeter was an interesting experience. Despite now being nearly rush hour, most of the route was on towpath still – some of which I recongised from walking with Yoli and Ben. Only a short stretch through the far side of town was on a busy-ish road. And, as with most roads West out of Exeter, it was up a long slow slog of a climb. The road was wide enough for traffic to pass though, and eventually, near the top, I branched off onto quieter back lanes.

Quieter they may have been, but flat they were not. I began to sense I may have dithered just a little too long at the start and was now going to battle to make my target campout area before dark. The scenery was stunning, which did make the riding enjoyable, but adding to the worry over time were the ominously dark clouds rolling across the higher ground ahead. Where was the sunny afternoon and clear night skies promised on the forecast? Subtle nagging doubts found their way into my spirits, and I was reminded of how easily the immediate physical battle can become less of an issue than a growing inner mental battle.

I’d set my sights on a drink and snack stop at the Whiddon Down garage that we visited as the second control on the Dartmoor Ghost. No having exactly checked the distances though, it took way longer than I expected to actually get there. More problematic still was something that had not been apparent at 2am in the morning. It was actually a Services pitstop for the nearby busy A30, and it was packed. It didn’t take a maths genius to assess the effect of the “1 inside the shop at a time” sign outside the shop, with the queue of 10 or 15 people already waiting. Without even bothering to dismount, I swung a loop around the petrol pumps and headed straight back out.

I couldn’t remember the exact distance between here and Okehampton, but I knew it wasn’t that far. My mind had a dim but definite recollection of another garage, maybe a BP, somewhere before there. Once I was on the Granite Way I doubted if I’d see anywhere to fill up. I’d need to suffer whatever queue was there rather than risk getting nothing before hitting the open moor. Luck was on my side though – there was no “1 person inside” policy and, probably because of that, no queue. I didn’t need much – just full water, a 500ml spare in my back pocket, and a pork pie and chocolate milk as energy for the remaining 40km or so of the journey. I should also add, at this stage, some uncertainy over both my planned evening meal, and available water supplies for the morning start the next day. I couldn’t be sure how well the JetBoil would work, if at all, or how palatable the freeze dried meal would be. In theory my filter could deal with practically any water source, but that depended on there being something not-totally-stagnant nearby. All of which were unknowns which is, of course, the whole point of having a test ride in the first place. Despite being near to home with bail out options, there was still a definite sense of vulnerability, of being ‘out there, alone’. I guess without that though, there’d be no adventure.

Okehampton did, as expected, arrive just after the garage stop. I swung right and up the steep roads of the town rather than weaving along the river as the Dartmoor Ghost had. I was keen to ride the whole of the Granite Way this time. It didn’t take a GPS to know I was going the right way. At some point the house-lined street I was slogging up and out of town acquired the name Station Road. Although the cycle route sign had me veer off and up a zig-zag path just before actually reaching the old station.

The Granite Way follows another old, Beeching-vandalised rail route. At it’s start though, it is still a railway – albeit another private enthusiast run operation, much like one I recently encountered on my coast-to-coast excursion to Watchet. Some time back, I thought I read something about this particular line, the Dartmoor Railway, being up for sale. I doubted it’s fortunes had improved much with COVID restrictions. Despite a surprising number of buildings and infrastructure, there were no obvious signs of recent activity or trains. Once I was beyond these and the town, I found a semi-secluded spot in a nearby stand of trees to strip down and don a warm base layer, and leggings for the growing evening chill. I was only just decently dressed when a group of girls, who looked to be in their early twenties, rode past. Seconds earlier, and my evening could have come to an akward end explaining to a policeman why I had been lurking in the bushess, exposing myself to passers by. OK, I never actually removed my cycle shorts, but it’s easy for such random encounters to get mis-interpreted.

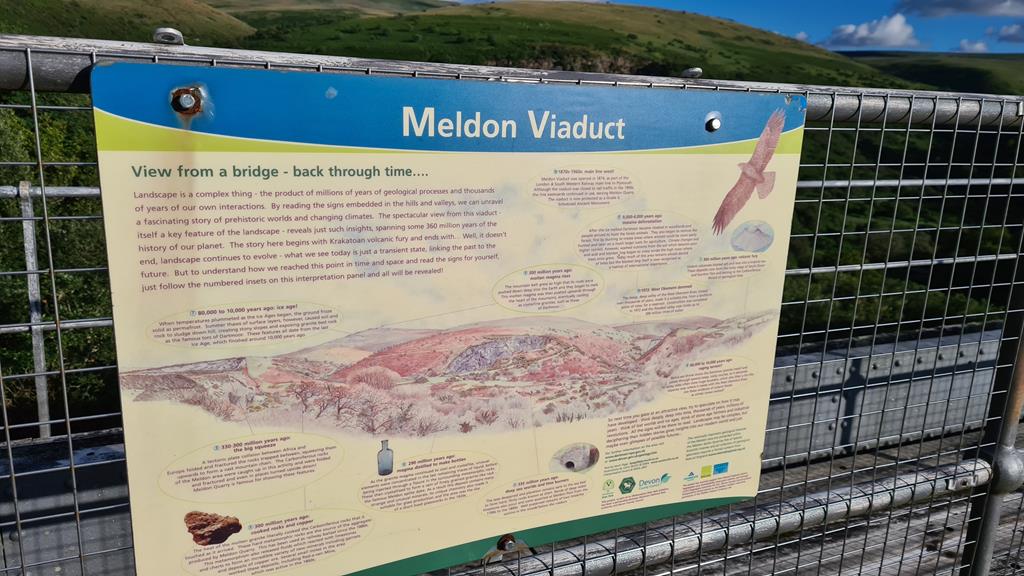

Surprisingly, this being the first Friday evening the pubs had been allowed to re-open, the cycleway was busy with riders and walkers. It was pleasing to see so many out enjoying the wonderful path and sunny, if cold, evening air. I knew the still-working part of the railway ended at the imposing Meldon Viaduct. What surprised me however, was the size of the marshalling yard just before it, and the amount of rolling stock which it still contained. The greater part of the coaches and wagons were in various stages of decay. Behind the very few grimey glass panes still present, and the empty holes of the remaining windows, an odd jumble of random shapes, and pieces of wood were just visible. It was as if every carriage had become a dumping ground for all the furniture and assortment of items that scrapping the line and it’s stations had produced. At the far end of the yard was a small cluster of coaches in much better condition. Tidy livery, no broken windows, and not plastered in graffiti. I guessed that these were probably the ones used for the occasional services that still managed to run for holidaymakers and the like. The greatest shame of all though, in a sense, was the abrupt end of the tracks before the viaduct. Whilst it marked the start of the best part of the path for us, as cyclists, it also meant any potential rail travellers could no longer venture along the most scenic part of the line – the edge of the moor itself, it’s vast expanse coming into view from the very start of the viaduct.

Only a little way beyond the viaduct, my route ran into the section that we’d taken on the Dartmoor Ghost, but in daylight it was completely different. The dark shadows of that eerie moonlit flight had become a glorious, lumnious green tunnel of trees. All around, small previously hidden details alongside the track now jumped out demanding attention: a sign reading “Waterloo 200“, amusingly charted the exact distance back to London; a succession of stone benches made from remnants of the line; an old railside shelter that might have made a good spot for a nap, had it been night, and not stunk of pee; and a steady succession of ponds. I wondered if these had been usd to fill the water tanks of steam locomotives – whatever their purpose, it must have been important since beside each was a small plaque with their name.

Somewhere just before the end of the path at Lydford, I came across what was presumably the reason the Dartmoor Ghost route did not follow the whole of the path. A rough gravel section with a sign stating that it was only open part of the year by permission of the landowner. Even if it had been open, the surface would have been sketchy in the dark, on road bike tyres. But in daylight, on gravel tyres, it was perfectly rideable. Finally, about 20km after Okehampton came the end of the delightful, fast, flat cycling. Once through the village itself, the road pitched steeply down and back out of one end of Lydford Gorge. A surprising distance further along, it did this again with another a brown viewpoint sign saying the same – only this time with an added “Waterfall End” or somesuch. I made a mental note to mention this to Yoli as somewhere to explore.

From here on, the road began to roll up and down near continously. For those parts where it was, actually a road. As the shadows grew longer, and the sun dipped out of sight behind, I found myself on a rough, rutted and rocky path. It was lovely, but not close to rideable on a heavy rig without full mountain bike tyres. One spot did nearly tempt me into bunking down for the night – a wooded glade, beside a babbling stream, with a clear section of bank to bivvy on. But I wasn’t close to the moorland where camping was permitted yet, so it’d be an illegal stealth camp, and in fairly close proximity to a group of houses. I pushed on and up until the path became an actual rideable lane again, at the start of a small village. After a brief call home to Yoli, the nearby “community playground” caught my eye. The massive wooden wendy house reminded me of a TCR rider, who was so tired they camped in a tree house in someone’s garden. Had it been dark, I might have been tempted, but instead I started on yet another climb in the last orange rays of daylight.

Passing a campsite on the right, another long but thankfully not too steep hill began. Except this time, I could see from the road ahead the open moor. At last I was reaching the area that wild camping was allowed. I knew I wouldn’t make the spot I had originally intended before dark, but rolling across the last cattle grid to be surrounded by bracken, gorse and heather clad moorland was a huge relief. After a couple of parking spots full of campers (not tehnically allowed), I crossed a stream that ran off into nowhere to my right. Apart from a steep bank down, it was an ideal spot. The stream was flowing well enough to be already decently clean without the added safety of my filter. I wandered a fair distance along the gently sloping grass bank until I found a likley looking spot. The road was far out of sight behind me, meeting the wild camping regulations, but more importantly added to the sense of complete peace and solitude. I stowed the bike and began to unpack my gear.

Overall the camping experience was remarkably seamless, and fairly quick, but not totally without issues. The JetBoil proved to be accurately named. It fired up instantly using the piezo button, and barely seemed to take much longer for the water to reach boiling. In the handful of minutes my meal was re-hydrating, I unrolled my bedding, and stuffed the now inflated mat and sleeping bag inside the bivvy. And here I hit my first small snag – nowhere to comfortably sit. In the end, I sat on top of the hood of my bivvy as a way to keep my bum dry (although I had put on waterproof shorts by this stage). The other, again minor issue, was not having flip flops – it would have been much more comfortable and less likely to tear anything important than cleated riding shoes.

For a freeze dried meal, the Pasta Bolognaise wasn’t actually bad. It didn’t even need any of the salt or chilli flakes I’d packed as a precaution against blandness. It was also fairly filling too, which seemed pretty important given the energy I’d burned over the tougher than expected climbing. A rather smug sense of satisfaction came over me after eating, and calling home. The light finally faded, and I shuffled fully inside the sleeping bag.. Somehow or other, pretty much all of the kit I’d packed had worked, and despite my earlier worries, it had all timed nearly to perfection. I lay there, my head resting on my saddle bag, staring up at a sky completely filled with stars. The forecast had even turned out correct, not a single cloud in sight. So low down though, and alongside water, that did bring on a surprisingly cold and damp night air. Before drifting off I pulled my shoes, phone, and battery packs into the hood of the bivvy behind the pillow to try and keep them from becoming totally soaked.

I’d be lying if I clamed anything like a full, restful night of sleep. My body was warm as toast, but my legs and feet were a shade cold. A breeze occasionally wafted around my face. But I drifted in and out of a few bouts of decently long unconciousness. A part of the problem was excitedness – it was tempting just to stay awake and gaze at the night sky and open moor in wonder. Another part was the interesting sleeping cocoon. At one point I dreamt was battling to scale some great wall, only to wake up and find my bivvy vertical alongside me thanks to slipping off the matt and it now acting like a giant inflatable tent pole.

Back – 11th July 2020

On one of the wakeful spells a faint ring of lighter blue spread along the hillside behind me. The dawn light was edging slowly over the landscape, and I got up with it. My plan was to get rolling early, but by the time I had filtered water for my bottles and eaten breakfast, it was already fully daylight. It took me way longer than expected to get packed, although at least I had a fairly decent cup of coffee whilst doing it.

A little after 6am, I trudged back along the stream and up the steep bank to the road. My hands were pretty cold after the damp pack up. I had gloves, but they were the type with removable inners. Like a couple of stubborn nightclub bouncers, they just refused to let my fingers back in a second time as hard as I tried to wiggle and untangle them. It was a truly stunning early morning to be out for a ride though, so I focused on the beauty of that rather than my surly handwear.

After rounding just one corner, the road dipped quickly down into the hamlet of Merrivale, which had been my notional target for the camp out. I guess I could actually have checked this on the GPS the night before, and the pub might even have been open for a drink. Although the temptation of that hospitality could well have completely eroded the whole test camp experience, so I was kind of glad I hadn’t. As if to confirm this possibility, there were a couple of tents pitched withing staggering distance of the pub’s front door.

A long and very demanding climb wound up out of the vale. Just before it’s top was a stone track leading off to my exact original destination. It was too far off to read easily, but there were some warning signs on a gate part way in. I wondered if, this being mining country, that perhaps it wasn’t as open or safe as the wild camping map had suggested. Or perhaps, it was simply too close to Dartmoor Prison. Either way, I was rather glad of the alternate spot I had found.

The rest of the morning’s riding is a close parallel to that on the morning of the Dartmoor Ghost – which is to say, relentlessly up and down, but with stunning scenery to compensate for the effort. I knew though, that once I dropped down to Moretonhampstead, the bulk of the climbing should be done for the day. Unfortunately though, I was too early for a cafe to be open for a second breakfast, so I blasted along the Wray Valley trail, with the hope of something hot and tasty in Bovey Tracey.

I wasn’t disappointed, as I exited the park onto the main road, I could see parasols being opened at the Bridgeside Cafe along the road. As I stood waiting at the crossing, a guy in shorts and a T shirt struck up possibly the most unlikely conversation of my entire life, which started with:

“Hi, you’re Rob right, we met in Exeter last night. How was your wild camping?”

It was the Pinarello rider who I’d stopped next to at the dual carriageway crossing the evening before. Except this time, he was on his way back home from walking to the shops. Both the timing, and the simple fact that he’d even be from Bovey Tracey still seem so improbable that I wonder if I imagined it. Perhaps I hadn’t slept as well as I thought, and this was an earlier than usual onset of the long distance cycling, day time delusions. I am fairly sure he was real though – mostly because as I sat drinking tea, and wolfing down an enormous plate of cooked breakfast, he was stood talking to the owner. The food tasted real enough, and there is definitely a charge to my credit card for the meal to prove some of this actually happened.

I need to start this next bit by saying I have absolutely nothing against e-bikes. My wife rides one, and I think they are a brilliant way to encourage more people to get out and ride, especially in hilly areas, such as the west of England. I also have nothing specific against the guy hurtling up the ramp of the cycle bridge across the busy Devon Expressway. In fact, as he picked himself up off the ground, and put the various bits of his bike back together he seemed like quite a nice chap. He didn’t run into me, but as he reached the right angle corner he was motoring. I looked straight into his startled eyes as a mix of too much speed, too little concentration, and a lack of bike handling skills all met on that too-sharp bend. His front wheel folded under him, and he hit the deck hard. I helped him up, and get straight, of course. But he was clearly embarassed, and in a hurry to be somewhere other than there.

What came next was almost as surprising, albeit in a rather more pleasant way. I had intentionally plotted the route along cycle ways, but I hadn’t expected such a long stretch of wonderful flat riding through woodlands and fields. It started immediately over the bridge, initially following a stream down through a natural reserve, and then seeming to follow the route of a disused canal. I was heading out of Newton Abbott in no time, barely having touched a road. I did make one slip-up though – a tempting looking bridge at the end of this stretch led left over the river, with a cycle path sign. But my plotted route went on. I very nearly made the decision to go off piste, and soon enough regretted having not done so.

The route slowly degraded, cracked tarmac, overgrown paths, industrial estates, and once across the road I had a sense of being somewhat on the wrong side of the tracks. I probably wasn’t but, despite the hill, I stepped up my pace to get back onto country lanes. It didn’t take long, but although it eased my nerves, it did nothing for my knees. Somehow, I had missed how up and down this section was. None of the hills were long, but they were numerous and painfuly steep. It took me an age to reach the coast, and the low bridge crossing the estuary at Teignmouth. It was immediately apparent too that my hopes of flatter riding were going to have to wait. A long, slow slog of a hill started immediately out of the town, followed by another soon after before finally reaching the outskirts of Dawlish, from where I knew it would get easier. In truth, none of this section would have been bad, had it not been for the climbing already in my legs, and the weight of traffic making the riding more stressful.

The rest of the riding was familiar, and largely unremarkable. Heading through Dawlish Warren I chatted briefly to a chap on a fully loaded touring rig, front and back panniers. Clearly a man who enjoyed his comforts, he had a radio on his front bags which was tuned in to the West Indies test match at Southampton. Our destinations were not far apart (he on his way back to Ottery St Mary), but our riding speeds were not a match so I bade him farewell and headed off onto the estuary cycle path.

Shops and cafes were busy, and I began to wonder if my favourite coffee spot in Topsham would be too crowded to be worth the wait. But, luckily, they were still only doing take away service, and had almost no queue. As I stood enjoying my coffee, and orange juice, a chap remarked on how tidily my bike was rigged. I soon learned he was also a keen cycle tourer, and in fact a part of his business was organising local and foreign tours. We chatted at some length before his order also arrived, and he headed back to his wife and their touring Tandem (a lovely Thorn). Pleasing as it was to have positive recognition of the bike setup from someone with experience in the field, even more rewarding was how well the full ensemble had stood up to a proper test. One thing that had surprised me was how well it rode, in spite of the added weight. If anything, the front of the bike felt less skittish and tracked better with the added load. The fatigue, and growing heat, faded in their significance. It was simply a great day to be out riding, and even better to do so with confidence that at least my kit was prepared for Scotland.

Rig Details

Cutting to the chase, this link details my, largely finalised, rig for the upcoming Highlands to Home adventure ride. At the core, it’s a fairly similar setup to that which I rode on TCR. But this year’s ride is, quite intentionally, not TCR, and that difference is reflected in the rig.

- Less need for spares and contingencies – there’s no disqualification here for accepting outside help.

- A desire to try out some wild camping, conditions permitting. There’s no real need for this. My route passes many proper hotels and B&Bs. But with a view to considering future bikepacking rides, or just some bike touring, I’m curious to see what a minimal set of outdoor sleeping gear consists of, and how it stows on the bike.

These changes add up to a very different rig:

- Somewhat more gravel oriented tyres – to encourage more offroad exploring

- A handlebar “roll” bag, containing a bivvy, sleeping bag, and other warm overnight gear

- Fork bags: one containing a Jet Boil, spork and foldable cup; the other containing food, and of course coffee.

- Katadyn water filter – reducing the need to always find a tap or a shop by making use of the streams by the side of the road.

- Shovel – for the obvious, leave no trace right! Gross, sure, but at least they come in orange,

All of the above thought are a big experiment. I’ve no real idea if this is a style of riding I’ll enjoy and plan more of, or whether I’ll fall back to the Audax or TCR riding styles I’m familiar with. As a result, I didn’t want to lay out a ton of cash on the extra pieces. As luck would have it, just as these ideas were slowly permeating my thoughts, Planet-X were promoting various parts of their bikepacking ranges with some massive special offer discounts. As with everything they sell, they offer incredible value. I must say too, based on the limited experience of the bags and Jet Boil, they also seem reasonable well made and very functional.

Removing that threat of disqualification or failure, relaxes some of the packing paranoia over having so many backup systems:

- Just one front light. The backup is a Petzl Actik Core headlight – main use being as a camping light, but bright enough as an emergency riding light.

- No handlebar mounted second GPS. Instead, I have my Samsung phone in a Quadlock case, with the mount ready on my stem in case of emergencies.

- No spare tyre. In it’s place, I have a selection of lighter, easier to carry repair options.

After years of riding with two or three of everything, it’s a real mental battle to let these go and at the last minute I may well cave to my need for a sense of security.

Ah, truth be told, I turned a pale shade of green when looking at your route. So many cool places – JOG, Cape Wrath, Loch Ness, Fort William, Glencoe-007, the list goes on and on. I also spotted a few fimiliar names further down – Lockerbie, Gretna Green, Carlisle.

What was the nighttime temp while bivvying?

Glad you weren’t caught with your pants down next to the railway – such antics might cause one to become known as ‘The Dartmoor Exhibitionist’. At least the shovel would have helped to explain your case.

PS, really looking forward to following your ride starting next week…

Haha – yes, no desire to acquire such a nickname.

Good Q on the temp – I meant to include a note. I thought it went down to 6C, but friend who also happened to be out camping I think said they may have recorded lower. It felt colder for sure with the damp air!

Yep – big bike clean and pack up this weekend, then we’re almost set. Hold thumbs no more COVID lockdowns!